“The Stones Will Cry Out”

Jul/12/2011 Archived in:Armenia

Muriel Mirak-Weissbach – July 11, 2011

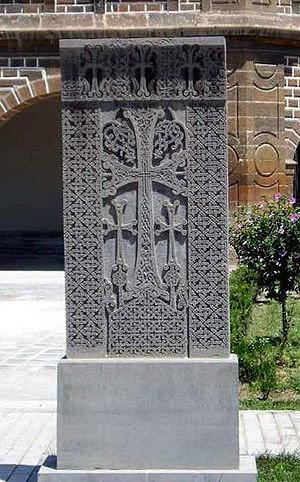

A scandal erupted in mid-June and marred an exhibit in Paris at UNESCO which featured traditional stone crosses from Armenian church architecture known as Khachkars. These unique sculptures and reliefs had been included in the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in November 2010.(1) The exhibit, co-sponsored by the Republic of Armenia’s Culture Ministry and inaugurated in the presence of numerous diplomats, artists, historians, and clergy, would have celebrated a magnificent tribute to the Khachkar tradition had it not been for the fact that at the last minute UNESCO erased all mention of where the stone crosses featured in photographs were to be found. The explanation for the elimination of the place names locating the pieces, as well as of a huge map of historic Armenia designating those locations, was that, since the Khachkars were not all on the territory of the Republic of Armenia, but could also be found in present-day Azerbaijan and Turkey, it would be better to maintain silence.

But, there is no way to maintain silence: “The stones will cry out.” And they did. Representatives of the Collectif VAN (Vigilance Armenienne contre le Negationnisme), present at the opening, protested with an open letter to Irina Bokova, Director General of UNESCO. (2) In the letter, they argued that not only does it violate academic practice to fail to mention the location of art works in such an exhibit, but, by ignoring their location, the exhibitors were rendering themselves complicit in a wild distortion of the historical record. To ignore the place names is to conceal the historical presence of the Armenian people and civilization in that vast region.

Travellers through eastern Anatolia and present-day Azerbaijan will find some Khachkars in their places of origin – although thousands have been deliberately destroyed -- and will make the historical connection.(3) I It is not only the beautiful stone crosses but the wealth of religious monuments -- be they chapels, churches, cathedrals, or monasteries – populating that geographical region that bear testimony to the physical and cultural presence of Christian Armenians since the fourth century. As Italian art historian Arpago Novello identified, this religious art was an integral part of the Armenians’ identity. “The Armenians’ tenacious attachment to the Christian religion,” he wrote,” testified by the thousands of crosses erected or sculpted almost everywhere and for every occasion, and by the extraordinary wealth of sacred buildings, was not merely a spiritual matter but a prime feature of their very identity and a symbol of their physical survival.”(4)

Yet that very presence is subject to denial and distortion. My brother, my husband, and I experienced this during a journey through eastern Anatolia in May. In place of the historical record we encountered mythology, with its own personages, events, and causality. In this mythological landscape, we were not in historic Armenia, let alone Western Armenia, but in eastern Turkey, in one of the Anatolian provinces, and everything we might have expected to recognize from past historical accounts had disappeared or had been transformed into something else, often into its very opposite.

We were travelling as part of a small group of Armenian Americans who sought to retrace the steps of parents and ancestors, to visit their villages and towns where they were born and lived before the genocide. It was like putting together a jigsaw puzzle. We had scattered pieces from our parents, like names of villages, descriptions of some localities, and we had read the accounts of eye-witnesses to the Genocide, like Johannes Lepsius, Jakob Künzler, Ambassador Henry Morgenthau, and others. But when we looked at a present-day map of Turkey, we more often than not found nothing resembling the place names. Our German guide book did not offer much help.

Without Armen Aroyan, our tour guide who has 25 years’ experience in accompanying pilgrims through the region, and our driver, who spoke both Turkish and Kurdish, we would never have found our way.

By asking at various points along the way, we did find Mashgerd, my father’s village. We learned it is no longer Mashgerd but Chakirtash, as the sign indicating entry into the town indicated: Chakirtash Köyüne (community), it said, Hos Geldiniz (Welcome). My father spoke of the Old Country in rapturous terms, telling us that the mountains, rivers, rolling hills, and green pastures in Maine in northern New England where we had a summer home, reminded him of those childhood surroundings in Mashgerd. His aunt, Anna Mirakian, who found him after the war and took him to America, described the town’s rich landscape in her memoirs as a paradise on earth. “The people of Mashgerd,” she wrote, “having abandoned their homes, fields, farms, orchards, and gardens, were being deported with broken and inflicted hearts from their heaven-like birthplace with tears in their eyes.” (5)

The mountains, green hillsides, and rivers were still there, but the size of the village has shrunk considerably. As soon as we climbed down from our minibus, the local villagers streamed out of their modest homes to greet us, displaying the same warm hospitality we were to receive everywhere. They offered us Ayran, a yogurt drink which we knew as Tun, as well as tea. They asked if we had come to look for buried treasures, since many Armenians had buried their valuables before being deported, in hopes of recovering them at a later date. No, we assured them, we were not seeking buried treasures, but treasures of another sort.

Here in Mashgerd what we were looking for was the church in which, as my father had recounted, the townspeople had been locked for four days before being taken out to be killed. “There is no church here,” the villagers told us to our dismay. There was a church some kilometers away that we could reach on foot, they said, but none in the town. That church may have been the St. Sargis cathedral which my father’s aunt wrote about. In her memoirs, she referenced a magnificent church in what was called the Lower Village: “Located on the banks of the Euphrates, Van Gyugh was a beautiful, lush green village,” she wrote. “The magnificent and glorious St. Sargis cathedral, where Easter services were held every year, was located there.” (6) But that was not the church my father meant. No, he said it was in Mashgerd, near the center of the village. Although the villagers had no knowledge of such a church, we knew there must be one, first, because wherever there was a sizable Armenian community there was a church or at least a chapel; secondly, because my father had written about its being in Mashgerd. And, his aunt had also spoken of a church there right in the center of the village.

After a long while, a very, very old man then appeared and said, yes, in fact, there was a church – kilise – in the town. He led us down a dirt road, past a fountain, and pointed to a large structure which at first did not look at all like a church. It was not shaped like other Armenian churches we knew, with their round central structures mounted on dodecagons or other polygons, rounded arches, and conical domes, but was oblong and had a flat roof. Then the old man pointed to certain bricks cemented into the façade, which had undeniable Armenian characters inscribed on them: names, dates, and khachkars; they were stones, our guide Armen explained, which had perhaps been taken from the cemetery and used in building the church, according to a custom known throughout the area. Or, they were bricks with khachkars designed to be part of the façade. So this was indeed a church, and it must have been the one my father knew! The shape of the church turned out to be one of many traditional Armenian church designs, known as the “long church,” and was similar to those churches in Artsathi, north or Erzerum, or to the one in Dirarklar.(7) Both are unadorned, with no round apses and had wooden roofs.

Back in 1916, when the people were let out of the church after four days and taken to the center of the town, my father who was eight years old at the time had run for his life, and managed to reach his grandmother’s house about 100 yards away. Her house had a stable in the back where he hid. I walked that distance in several different directions from the church and the nearby central square looking for a dwelling that would fit that description, and I found several. Which one might have been his grandmother’s house? His aunt also referred in her memoirs to her “ancestral Kokats – hay and stable – located in the center of the town,” which might have been the same dwelling. Which one was it? There was no way of telling.

Locating Tzack, my mother’s village, was not so easy, also because it was no longer known by that name, but was called Inn in Turkish. How different it was from her descriptions! At that time, there were about 100-150 families in Tzack, now, the villagers told us, the only inhabitants were 3 brothers and their families. An old woman, well into her 70s, welcomed us warmly and, hearing that we were Armenian Americans, told us that she herself was half Armenian. Her mother had been saved as a child and been married off to a Turkish man. “I remember only,” the woman said, “that she always cried. She had lost everything, everyone, all her family.” She went on to tell her own story. “I too was married to a Turkish man,” she said wistfully, “and as a bride I also did nothing but cry.” Visibly shaken by the recollection, she excused herself: “I have high blood pressure and cannot speak much longer.”

My mother’s grandfather had been a well-to-do landowner with rich agricultural land including vineyards that covered the hillsides. All I saw was one lonely wine stock twisting up a stone wall over a gate supporting a thatched roof to the woman’s house, with some grapes hanging down. Two or three chickens trotted across the dirt path, looking for something to peck at. Peering behind the house with the grapevine, I saw a terrace with bee hives and bees swarming around. I remembered that a cousin of my mother’s, the son of the woman who had found her and taken her to America, always kept bees in Watertown, Massachusetts, and would bring us honey combs. This was apparently a family tradition that they had maintained from the Old Country.

As we walked down from her dwelling and reached the main dirt road, we saw on the other side of it a vast plain studded with ruins of buildings. Stones, two or three piled on top of one another in neat rows, stood there where houses had once been, all organized in blocks, with walkways or streets in between. The stones were the remnants of homes, shops, and businesses in a highly developed settlement. Walking along the grass was like picking one’s way through stone foundations of ancient Roman settlements.

Another piece of the jigsaw puzzle was Agin (Agn), the town where my mother’s adoptive Turkish parents lived. There are two towns with similar names, one south of Arabkir, the other, to the north. Armen reckoned the latter must be what we were looking for, since it was within walking distance (perhaps several days’) from Tzack, which dovetailed with my mother’s account of the distance. Today it is known as Kemaliya, named after Mustafa Kemal. The story goes that after a visit to the place, Ataturk reportedly raved about how lovely it was, whereupon it was renamed and restored. It was nothing like the other villages we had seen. The main street was lined with beautifully renovated wooden facades, giving it the air of a Swiss chalet ski resort. There was a building housing a museum which bore the unmistakable architectural traits of a lovely Armenian church with its graceful arches.

What we were looking for in Agin was the mosque on whose steps a Turkish shepherd had laid my infant mother. He had found her, the only survivor among a field of corpses of women and children who had been taken from Tzack and shot. As was the custom with foundlings, he took her to the town, perhaps his home, and left her on the mosque steps, where a gendarme named Omar found her and took her in. Omar’s wife, who was childless, did not want the baby because it was Giavour (Christian), and because she felt she was too old to bring up a child, so she took her back to the mosque the following day and placed her again on the steps. While Gulnaz chatted with her lady friends, the child crawled over to her and tugged on her skirt, which she took as a sign from Allah that she should take care of her, and she did.

The mosque was very old and very beautiful, built in 1070, restored in 1960 and again in 2005, located in the center of the village on a street going up from the main street. In front of the mosque was an open area like a small piazza, which was where perhaps Gulnaz and her lady friends had sat.

On the way to Erzincan, where we would spend the night before proceeding to Kars, we stopped at Kemagh Gorge. Standing on the bridge over the river, we gazed up at the rocky ledges on both sides. It was from those lofty heights that Armenian men, lined up two by two and tied by the wrists, were thrust down the gorge, after having been bayoneted in the ribs by their murderers.(8) Although the name Kemagh Gorge rings with an ominous tone to the ears of anyone familiar with the history, a newcomer to the site would have no way of knowing what he was seeing. There is a plaque fitted into the stone on one side of the bridge, but it makes no mention of the tens of thousands of Armenians pushed to their deaths into the river. Instead, the plaque commemorates six Turkish soldiers who had perished in a tragic automobile accident some years back.

In Zatkig, a village along the road to Kars, we came upon another small church bearing testimony to its Armenian past. In 1915, that province had a population of about 150,000, ten percent of whom were Armenian. On the wall of the 10th century church, though in ruins, were bits of frescoes visible, painted in blue and white. Stones had been walled into the formerly open arches, and the structure, also of the long church type, was now being used as a storage place for wood. From the abundance of hay in the back, it appeared that it may also have been being used as a stable.

A similar image greeted us just prior to our entry to Erzurum, a city that was part of the ancient Armenian kingdom at the end of the 4th century: the ruins of a church with grass growing on what once was its roof. It looked like hair sprouting from the head of a Benedictine monk which should have been shorn.

But in Kars, our next stop, the church we visited stood out in magnificent contrast. The Apostles Church, built by King Abbas in 937, had been turned into a mosque in 1064. For a brief period of forty years beginning in 1878 during the Russian occupation, it served again as a Christian place of worship. At that time the Russians built on four porticos at four entrances, adding a distinctly Russian flavor. Then it was a museum between 1969-1980, and again became a mosque in 1994.

But there could be no mistake about it – this was a church. The majestic reliefs on the upper portion of the façade under the dome between the arches are easily identifiable as the twelve apostles, at least, to anyone familiar with church architecture and iconography. The sign in English, placed there for the benefit of foreign tourists, gives no hint as to who worshipped there before it became a mosque. It said the church had been built by one “Bagratid King Abbas (932-937)” and listed its subsequent functions. The word “Armenian” was nowhere to be found. Who the Bagratids were was left to the imagination.

The same mythological reality greeted us at Ani, the magnificent ancient city which once was the capital of the Armenian kingdom. Two large plaques on the side of the city’s ancient walls inform the visitor of Ani’s long illustrious history, again without reference to the word “Armenian.”

It was Ashot III (952-977), king of the Bagratids, who built Ani, the capital city “with its 1001 churches.” This was clearly a metaphor, but just as clearly evidence of the fact that a large number – hundreds – of churches had graced the rolling hillsides and nested in the cave-like apertures along the steep slopes of the gorge down to the Ahurian River. One such edifice was the Church of St. Gregor of Abughamrents, erected in the middle of the 10th century, perhaps by Abughamrents Pahlavani. The structure based on a dodecagon ground plan, is still standing with its dome, though the lower portions of the external façade are damaged.

The Church of the Redeemer, completed in 1035-1036, was also associated with the Pahlavani family, built by Ablgharib, son of Gregor. The interior, which measures 15 meters in diameter, is articulated in eight large niches, all of them once graced with murals. The structure today is a shadow of its former self, literally a half circle of the original structure. But since historically accurate photographs from the later 19th century exist, reconstruction is eminently feasible.

The Church of St. Gregor built in 1215 by Tigran Honents, is a domed hall standing on a hilly mound. The triangular slit apertures and arch shapes on the facades appear here for the first time in Armenian architecture together as external decorative elements. This church hosts the most beautiful and best preserved frescoes both inside the structure and on the outer walls, frescoes that cry out for restoration.

And the masterpiece of church architecture in Ani is the cathedral, an imposing structure which, despite its advanced state of decay, still displays a proud sense of majesty. According to the account of a contemporary historian, Stephan of Taron in the tenth century, the Bagratid King Ashot died in 977 and was succeeded by his son, Smbat who ruled from 977 to 989. Smbat commissioned the master architect Trdat to build a magnificent church and he set about the task. In the year 989, the year of Smbat’s death, an earthquake hit Constantinople, causing immense damage to the Santa Sophia church. A crack in the wall had burst under the impact of the earthquake. One person who knew what to do was Trdat, a famed stone mason, who had drawn up a plan and had built a model of the Santa Sophia church. So he went to Constantinople and used them as the basis for its reconstruction. Once that had been done, Trdat returned to Ani, and set to work on the cathedral.(9)

When we left Ani and set out on the road to Van we were confronted with one monument which very prominently featured the word “Armenian.” This was something built between 1995 and 1997 in Igdir and modeled on the genocide memorial in Montebello, California; the Igdir structure honors the memory of Turkish martyrs killed by Armenian assassins. The monument, which houses a museum with numerous photographs, commemorates Turkish diplomats and other public figures who were assassinated by terrorists belonging to the ASALA movement. According to the plaques inside the building, up to one million Turks (!) fell victim to them.

The next stop on our itinerary, Van, boasts of an ancient history stretching back to 800 B.C. when the Urartuans built the massive walls and fortress which enclosed the huge settlement whose houses are now buried under mounds of earth. Van was also the site of a spirited Armenian resistance against the Young Turks in 1915, one of the few which succeeded. Nearby we visited the Varakavank monastery with its seven churches. Last year, the Archbishop Ashjian had complained that the site was unkempt, and had asked that it be cleaned up. Happily, with funds collected for the effort, local residents swept it clean, and we found it in orderly condition.

The highpoint of our pilgrimage was Akhtamar. This is perhaps the most beautiful Armenian church ever built, with its unique bas reliefs depicting scenes from the old and new testaments. Its harmonious architectural forms gain in majesty by virtue of its location, high on a hill on an island in the green-blue-turquoise-colored Lake Van, surrounded by snow-capped mountains. Akhtamar has gained special significance over the past year, both artistic and political. The façade of the church has been fully restored, including the bas reliefs, the most magnificent such restoration effort in Turkey. (10) And in September 2010, Turkish authorities allowed a church service to be celebrated there, for the first time in 95 years. An altar piece with a depiction of the Virgin Mary with child, which was brought for the first service, remains. Now the church should host the divine liturgy once a year. We were allowed to sing the Lord’s prayer (Hayr Mer) inside one chapel, but when Armen started filming the event, a guard told him to turn off the camera.

Though it defies belief, there is not one mention at the site of the fact that Akhtamar was and is an Armenian church. The architect was a monk named Manuel, who had built a palace for Gagik I, King of Vaspurakan, and between 915 and 921, he erected the church at Akhtamar. Though this is documented by historian Thomas Artsruni, there is no mention at the site today of who Manuel was, or what church he belonged to. This fact -- perhaps even more than the controversy surrounding the 2010 service, the disagreements regarding who should or should not attend, or whether or not the cross could or should be placed on the top of the church -- captures the psychological dilemma in official Turkey’s attitude towards the Armenian question.

The official refusal of the Turkish establishment to acknowledge the 1915 Genocide has led it to attempt to deny the very existence over a thousand years of an Armenian civilization and culture. Because to acknowledge the existence of that tradition would lead to the question: what happened to that civilization? Why was it destroyed? How was it destroyed? Thus to say or to write, “This was an Armenian church” is so charged with associations that one prefers to avoid the words.

But such an enterprise is futile. No amount of denial can eradicate the fact that such a civilization did exist in Anatolia since time immemorial. The stones do cry out, and increasing numbers of visitors from the Armenian Diaspora are travelling through the region and hearing the wonderful tales that the stones have to relate. Ordinary Turkish citizens, like the many we met during our visits to the villages and towns, had no problems in acknowledging the past. In Peshmashen on the way from Elazig to Arabkir, residents told us that their forefathers had been resettled there from Greece and the Balkans in the population transfer after World War I. They had been brought in to inhabit the homes and farms left empty after the expulsions and killings of Armenians. They swore that their forefathers had had nothing to do with the genocide and they were telling the truth. In Kharpert, local townspeople showed us historical photographs of the Euphrates College that had been replaced by another building. Many people spontaneously offered stories about their Armenian grandmothers, or mothers, as in Tzack. In Arabkir, the neighbors remembered with affection Sarkis, the last Armenian in the town who had died last year at the age of 95.

The problem lies not with the Turkish people. In fact, there is a wave of ethnic rediscovery sweeping across Turkey, whereby hundreds if not hundreds of thousands of Turkish citizens are uncovering their Armenian roots and working through their family histories.

The problem lies not with them, but with the Turkish establishment who, as Hrant Dink put it, has been suffering from “paranoia” as a result of the historical burden of the Genocide. To protect the paranoia, the Turkish establishment has perpetuated the fantasy of denial, even going to absurd lengths of trying to rewrite a history of the region which omits the Armenian presence.

As any clinical psychiatrist will attest, overcoming such paranoia must involve facing reality. This means acknowledging the historical record, not only recognizing the Genocide perpetrated by a specific Young Turk regime in a specific time frame and circumstances, but acknowledging the existence of the Armenian component – cultural, political, and religious – as an integral part of the history of what is today’s Turkey. The most appropriate approach would entail cooperative efforts by the Turkish authorities with Armenians, from the Republic of Armenia and the Diaspora, to restore and rebuild the artistic treasures of the Christian tradition, to rehabilitate that contribution to world civilization, and to reopen the houses of worship. The role of UNESCO should not be to provide cover for the distortion of history, but to let the stones cry out.

1. ^ http://www.unesco.org/culture/ich/fr/RL/00434

2. ^ http://www.collectifvan.org/article.php?r=0&id=55039

3. ^ Azeri bulldozers mowed down thousands of Khachkars in an Armenian cemetery in Jolfa, Nakhichevan, and the photograph of the cemetery prior to the destruction was displayed at the UNESCO exhibit.

4. ^ Alpago Novello, “Armenian Arachitecture from East to West,” in The Armenians, Rizzoli, New York, 1986.

5. ^ Anna Mirakian, Wounds and Pains: A Child-Bereft Mother, Aprilian Genocide Series, No. 10, p. 25.

6. ^ Ibid., p. 16.

7. ^ Josef Strzygowski, Die Baukunst der Armenier und Europa, Kunstverlag Anton Schroll & Co., G.M.B.H. in Wien, 1918. All the historical material pertaining to the church architecture mentioned in this article is drawn from this seminal work. Most valuable are the photographs in this work, all taken in the later 19th-early 20th century, long before the First World War. They show many of the churches as relatively intact. The cathedral in Kars, for instance, is shown before the Russian porticoes were added.

8. ^ Christopher J. Walker, “World War I and the Armenian Genocide,” in The Armenian People from Ancient to Modern Times, Volume II, Foreign Domination to Statehood: The Fifteenth Century to the Twentieth Century, edited by Richard G. Hovannisian, Macmailla, New York, 2004, p. 247.

9. ^ Strzygowski, op. cit.

10. ^ Etching of many of the Akhtamar reliefs, done by graphic artist Sartorius prior to the restoration, are available for purchase, and the proceeds go to finance continuing research on the Genocide based on documents of the German Foreign Ministry during World War I. See www.armenocide.net